Students raise awareness of missing girls, one story at a time

By Neal Christie

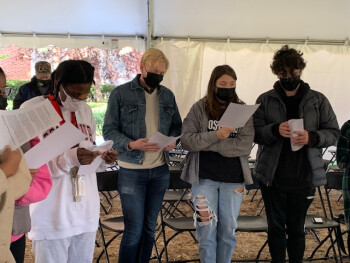

What would compel a group of twenty-five Frostburg University students to board a bus at the break of dawn one Saturday morning and drive to Washington, D.C.? And why would a group of Howard University students wait in the cold, under a tent outside, to welcome students they had never met?

What would compel a group of twenty-five Frostburg University students to board a bus at the break of dawn one Saturday morning and drive to Washington, D.C.? And why would a group of Howard University students wait in the cold, under a tent outside, to welcome students they had never met?

Jaques Metayer is from Hagerstown, by way of Miami and Haiti where her family immigrated from. She studies psychology and conflict transformation. It was Metayer to first introduced the idea that Frostburg United Campus Ministries hold an awareness campaign on Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG).

“We are here today,” Metayer said, “because last the summer I saw lot of news about bodies being discovered in schools that closed only recently. When I asked around campus, I realized I was not the only one. As a Black woman I know that racism still exists. When Chaplain Cindy asked what social justice project we wanted to get the campus involved in, and said that if we can make it happen we can do it, I realized that bringing awareness is where we needed to start. I had to remind myself that there is so much in the world to do. I cannot save the world in one day or alone—but I have voice.”

Metayer explained that before greater democratization in Haiti, her family was displaced and whatever records her parents possessed had been lost. Her mother’s wedding album was lost in an earthquake and floods washed away much of what her family owned. “It hurts to lose your history and not to know where you are from, she said. “I have seen too many Black women expected to be strong, resilient, the one whose shoulder you go to cry on. But then, when we speak up, we are told to suffer in silence. I do not want that to happen to Native American women in the church or in our country. They need to be treated with equity.”

In addressing the inequities, Chaplain Cindy Zirlott, who leads the Frostburg United Campus Ministry, reminded the students that God cares, and therefore we care.

“I did a summer mission on a Lakota reservation and an elder taught us a saying, “Mitakuye Oyasin” (pronounced mi-tahk-wee-a-say Oy-yah-seen) which means, ‘We are all related,’” Zirlott said. "We care because we are all related, if one is diminished or silenced, we are all diminished as a people, we all lose our value. Indigenous women cannot be forgotten because it would be as if human life has no value.”

“I did a summer mission on a Lakota reservation and an elder taught us a saying, “Mitakuye Oyasin” (pronounced mi-tahk-wee-a-say Oy-yah-seen) which means, ‘We are all related,’” Zirlott said. "We care because we are all related, if one is diminished or silenced, we are all diminished as a people, we all lose our value. Indigenous women cannot be forgotten because it would be as if human life has no value.”

“Each year, when our student leaders plan the year ahead, they have a category to consider, ‘Tikkun olam,’ or ‘repairing the world.’ We are called to partner with God in repairing the world,” Zirlott explained. “I ask them two questions at this time: What has God placed on your heart that needs repaired, and then, what can we do about it? This year, the focus to answer that question was Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls.”

When asked how many students were aware if they have Native American ancestry close to ten students raised their hands.

The facts are bracing. Twenty-two percent of American Indians and Alaska Natives live on reservations or other trust lands. The Center for Disease Control and Prevention report that murder is the third-leading cause of death among American Indian and Alaska Native women and that rates of violence on reservations can be up to ten times higher than the national average. No research has been done on rates of such violence among American Indian and Alaska Native women living in urban areas, even though approximately 71% of American Indian and Alaska Natives live in urban areas.

In 2019, more than 5,590 Native American women were reported missing. Murder is their third-leading cause of death, and yet there is still no single database that tracks the number of Native women who go missing every year. Those federal agencies that do collect data don’t keep track of nationality and too often Native women and girls are miscategorized as non-white or White.

The Urban Indian Health Institute (UIHI), a tribal epidemiology center based in Seattle, WA, says that in 2016 the National Crime Information Center reported that there were 5,712 reports of missing American Indian and Alaska Native women and girls, though the U.S. Department of Justice’s federal missing persons database, NamUs, logged only 116 cases.

The role of the church is haunting. Aggressive and frequently church-run residential boarding school systems forced children living in these school settings to adapt to the dominant culture. Some school officials baptized Native children, many of whom endured physical and emotional abuse and sometimes died at the hands of those who were charged with taking care of them. Displaced Native women have endured human trafficking and intimate partner violence.

Secretary of the Interior Debra Haaland has said, “Violence against indigenous people is a crisis that has been underfunded for decades. Far too often, murders and missing persons cases in Indian country go unresolved and unaddressed, leaving families and communities devastated. Currently, fewer than half of all federally recognized tribes receives Family Violence and Prevention Services support and under the Victims of Crime Act (VOCA) assistance programs from crisis intervention, mental health counseling, emergency shelter, criminal justice advocacy are unavailable.

How does our knowledge commit us to action? It’s a question Howard University students often ask themselves.

How does our knowledge commit us to action? It’s a question Howard University students often ask themselves.

Chaplain Alexis Brown, director of the Wesley Foundation at Howard, welcomed the Frostburg students and explained, “I was interested in learning how students would engage this issue and connect it with their own stories of struggle. I was happy to learn want they had to say and how our Campus Ministry could be of support.”

Dashawn Jones, a peer minister at the Howard University Wesley Foundation and mathematics major, welcomed the Frostburg students to campus. After asking how he could pray for them he explained, “the biggest thing I learned is that 80 percent of Native American women have faced some form of sexual violence in their lifetimes and for 86 percent of these women the perpetrators were not Native men. The system is unjust. Men take advantage of women who have been displaced. That needs to stop.”

Jones added, “As a person of faith, first and foremost, I believe we need to pray and then, as communities, we need to be compelled by God to stand in the gap and advocate for the protection of women at every level, the local, the state, the federal level.”

“I see a connection between the Black community and Native community,” he said. “All communities that have been marginalized need to come and stand together. … Once I know your story, I realize we have more in common. In the church I have heard and witnessed a lot of violence and it needs to stop.”

Amanda Stanley is a sophomore at Frostburg University and a mass communications major recently joined the United Campus Ministry because, she said, “It is where I get my spiritual food and coincides with my beliefs. I know people by their names here.” This was not her first time at the National Museum of the American Indian, but it was the first time that she noticed that the “Smallest images of traditional Native American art also had intricate designs and implied a much bigger story about who they were and today.”

Stanley started to hear about MMIWG and the more of the story behind the thousands of children who have been buried in unmarked church run boarding school graves in the U.S. and Canada and realized, “When will we get this right? Children and now, women today, have been taken away and it made me angry. Investigating those who have gone missing doesn’t happen and resources are stretched thin for tribes. These could be my sisters. Sometimes, I feel like a broken record because how can we not see how women are treated?” She is excited to keep the campaign going at Frostburg and include more students.

“I do believe that to every problem in the world there is a solution," Stanley added. "Churches can check in on families, we can provide legal assistance, we can expect our Congressional representatives to work on this. We need to know which legislative committees to speak to and where to find the facts. I was always reminded by an older woman in the congregation I grew up in that we need to find out what’s going on—because if we don’t stand for something we will fall for anything.”

Those interested in this issue are asked to support:

For more information:

To learn more about MMIWG:

- A Call to Truth Telling and Repentance from the Native American International Caucus (NAIC)

- We are Still Waiting--A Call to Action

- The National Native American Boarding School Healing Project

- Coalition to Stop Violence Against Native Women

- Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women U.S.A

- The Violence Against Women Act

- Savannah's Act

Well said. Violence always has a high potential to being misdirected often with victims being collateral damage. Whether violence may or may not have caused slavery is worth debating. The daily prayer that rings true is "deliver us from the evil of violence." Every child, woman, and man deserved to live in a place free from violence. Tornado shelters and early warning systems to have have people know when danger is imminent and where to go to be safe, that too could save many lives.