Old Otterbein celebrates 250 years of spiritual fervor

Old Otterbein UMC in Baltimore celebrates is 250th anniversary this year. The Rev. Cynthia Horn Burkert, co-chair of the church’s anniversary committee, shared this presentation at the Northeast Jurisdiction Commission on Archives and History on May 12.

Here is what we are celebrating:

In 1771 a movement of German-speaking Reformed Christians, seeking what would later be referred to as “a true spiritual life,” formed an independent church in Baltimore Town, in the Colony of Maryland. They purchased property at the corner of what is now Conway and Sharp Streets, and immediately built a wooden structure in which to worship.

Two and one-half centuries later, Old Otterbein United Methodist Church continues to embody the legacy of that group of German-speaking Christians. On the corner they purchased 250 years ago, their spiritual descendants still worship, celebrate, form disciples, and most importantly, go out in mission – a vital congregation for the 21st century.

Two and one-half centuries later, Old Otterbein United Methodist Church continues to embody the legacy of that group of German-speaking Christians. On the corner they purchased 250 years ago, their spiritual descendants still worship, celebrate, form disciples, and most importantly, go out in mission – a vital congregation for the 21st century.

Old Otterbein can claim to be the oldest church edifice in Baltimore still in use, built in 1785. But the building’s age does not give rise to this celebration. What we celebrate is both the spiritual fervor and the tangible commitments of a community of recent immigrants, acting in faith out of an evangelical or pietistic zeal. They could not have known that what they established would become the “mother” church for two strands of the Protestant family: the Church of the United Brethren in Christ and the Evangelical United Brethren (EUB). They could not have envisioned the 1968 merger of the EUB and The Methodist Church to form the United Methodist Church, and the subsequent designation as one of the denomination’s Historic Shrines. Now known as a Heritage Landmark, we are proud to be one of two in Baltimore, along with Lovely Lane.

In 1785, the original wooden building for worship was replaced by the gracious Georgian-style church we still occupy today. It is one of the four oldest structures to survive from the colonial and early Continental Era in Baltimore, along with the Carroll Mansion, Robert Long House in Fells Point, and a fourth structure originally used as a coffee house, that survives only as two of its walls have been incorporated into a commercial building.

On February 7, 1904, Sunday worship was interrupted by the clamor of fire alarms. The Great Baltimore Fire would destroy 86 blocks of the city and come within two blocks of the church. Because of its miraculous preservation from the fire, Old Otterbein has the distinction of being at the same site since 1771, and in the same building for 236 of those years.

As I dug into the story of those later colonial era immigrants, I learned that as early as 1758, there was a German Reformed Church in Baltimore meeting on Charles Street near Saratoga Street. Among Baltimore Town’s few thousand residents, it is known that there were so few Germans that the Town’s German Reformed, in larger numbers, and German Lutherans worshipped together, as they also did on the frontier. However, disputes arose when it came time to buy property and the resulting split yielded Zion Lutheran (founded in 1755) and the German Reformed Church, that would be located on North Charles Street. A minister came directly from Germany to take charge of the congregation in 1760, without being called by or having any connection to the synod, which was based in Pennsylvania. His name was John Christopher Faber and according to records of the time, he proved to be unsatisfactory to many in his flock. He was described as “formal and languid”, and was said to lead “an offensive life.”

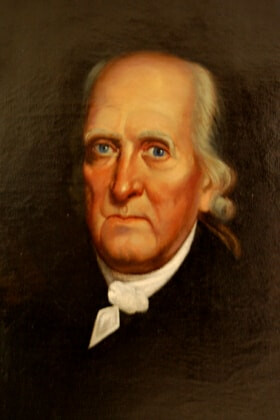

Philip William Otterbein was one of six young ministers recruited by Michael Schlatter, at around the same time. Because of a depression in Germany, his efforts were financed by Reformed Christians in Holland. Otterbein arrived at age 27 to serve churches in Pennsylvania and on the western frontier, where his service in Frederick, Maryland, was thus described in the Reformed church minutes: “He has almost worked himself to death.” Even though he was not to serve the church he inspired until 1774, in those intervening years Otterbein apparently preached often in Baltimore and inspired a growing evangelical faction within the Baltimore church.

These Christians’ growing desire for “a true spiritual life” came in conflict with the synod in Pennsylvania, which seemed unable to satisfy their need for inspired pastoral leadership. Indeed, various sources point to the uneven quality of ministers sent to the little church at Baltimore, although it is probably the case that the more outrageous the experience, the more likely the story survived.

The evangelical movement separated themselves under the leadership of Benedict Schwope, who preached his first sermon in November, 1771. If I read between the lines in Dieter Cunz’s The Baltimore Germans, it seems that the Synod in Pennsylvania agreed to recognize Schwope as a last ditch effort to keep the evangelical movement in the fold, but it was too late.

The new church community purchased four lots from the Cornelius/John Eager Howard families for 90 pounds ($240.30) and built a log frame chapel on what is now Conway and Sharp Streets. The group adopted the name, “The German Evangelical Church of Howard’s Hill”. Significantly, the deed was not executed in the name of the German Reformed Church, which firmly established this as an independent church.

The population of Baltimore Town at the time was approximately 5,000, most of whom lived to the east side. “Howards Hill” was open country from the church site to what is now the Washington Monument, about a dozen blocks to the north. Sharp Street was known as Walnut Street, where mature trees shaded a brick walk around the church.

A word about population and immigration trends might provide some of the context for the experiences of this little band of Christians. The population of Baltimore Town was about 5,000 and growing. The Port of Baltimore had been established in 1706, but for many years it was neither the major port nor the major point of embarkation for European immigrants. That distinction belonged to Annapolis, and the bulk of the immigrants were coming from farming regions and heading west, to wrest a living from a harsh frontier, primarily growing wheat.

By 1790 the population of Baltimore was estimated at around 13,500, whereas the Frederick County population was more than twice that, around 31,000. The growth of Baltimore’s German immigrant population was due in part to a reverse migration, as farmers took up trades or gave up on farming on the frontier, and returned to the growing Baltimore Town, which resulted in a corresponding growth in the church.

When I read what seems a tedious recital of one pastor after another sent by the synod in Pennsylvania, and subsequently rejected by the Baltimore Reformed church as lacking in zeal or dedication, or of pastors called by the Baltimore church, and rejected by the Synod, I can only conclude that Baltimore’s church was viewed as less important than either the Pennsylvania churches, or the churches in Western Maryland. Baltimore was still a bit of a backwater in 1771.

In the same period, even though he was “working himself to death” in Frederick and other places, William Otterbein was doing a bit of itinerating around the region. Before he came to the mission field of the colonies, church authorities in Herborn, where he was both preacher and teacher in the school, had attempted to silence him. His mother said, “My William will have to be a missionary; he is so frank, so open, so natural, so prophet-like. This place is too narrow for him.” Apparently, wherever Otterbein was assigned by the Synod, he found opportunity to preach in Baltimore, and his preaching stirred up in his hearers a fervor that likely contributed to the breaking away of this group seeking “a true spiritual life.”

You may conclude, as I have, that these awakened Christians were not content to be tied to a governing body in another state with allegiance to a church in Germany, who paid little attention to their spiritual needs. They were becoming Americans, and they would establish themselves in this new town, in a new world, with a new beginning.

The year after they established the new church, a pastor named Joseph Pilmore, who had been sent by John Wesley to organize Methodist societies in America, needed a place for his 40 Baltimore followers to meet. Benedict Swope made his chapel available to them. Indeed, from the beginning the church’s story was entwined with the history of the Methodists.

It was on this site that the Lovely Lane Meetinghouse congregation was organized in June 1772. Bishop Francis Asbury insisted that Otterbein be present at his consecration at the 1784 Christmas Conference at Lovely Lane Chapel, during which the Methodist Episcopal Church was founded. Four months after Bishop Otterbein’s death in November, 1813, Bishop Asbury came to preach a memorial service for Otterbein in the sanctuary. In fact, the existing structure is the only church in Baltimore still standing where Bishop Francis Asbury preached.

The year the Methodists built Lovely Lane Meeting House, 1774 – one year before the American Revolution began at Lexington and Concord – Pastor Benedict Schwope decided to take his evangelizing to the western frontier, which at that time was Kentucky. The church needed at new pastor, and Bishop Asbury persuaded the 48- year-old William Otterbein to accept. It is notable that he had previously refused the synod’s invitation to come to Baltimore, and also been refused when suggested to the synod.

He was to remain pastor of the church that would bear his name for 39 years, until his death on November 17, 1813. His tomb is on the south side of the church building.

The spiritual descendants of Otterbein and those spiritually-hungry Baltimoreans who set themselves down on a corner in Baltimore Town, live on in the community of Old Otterbein United Methodist Church, with its roots in the 1700s, and a vital and ongoing witness, across four centuries.

Throughout 2021, Old Otterbein will be celebrating under the theme of “RENEWAL: A True Spiritual Life”, in cooperation with the General Commission on Archives and History of the UMC and the Baltimore Washington Conference. Old Otterbein 250th Anniversary Committeeinvites you to participate in events throughout the rest of 2021. Links to worship, and a schedule of upcoming events is at oldotterbeinumc250.org.

A Capital Campaign to address current and ongoing restoration needs will be launched later in 2021 through Friends of Old Otterbein, a separate 501.c.3 corporation. Meanwhile, we invite you to become a member of Friends of Old Otterbein for modest annual dues of $20.

For more information: Rev. Cynthia H. Burkert or Daniel Fisher, president of Friends of Old Otterbein.