Traveling the Circuit: Willamette Heritage Center

By Rev. Charles Harrell

I am happy here, though I have not forgotten home and all its endearments.... Here I will live and die and be buried. God is here, and heaven is as near as at home.

Letter of Anna Maria Pittman (Lee) to her parents, 5 June 1837

Methodism’s influence sometimes surfaces in surprising places and unexpected ways. If your education was like mine, you were taught that the first settlers in the Pacific Northwest in the wake of Lewis and Clark were the trappers and traders following the Columbia River, following

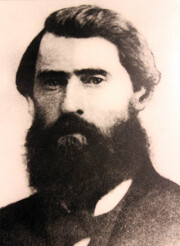

The Methodist story at Salem – Chemeketa, as it was known then – centers around Rev. Jason Lee, a native of Lower Canada (Quebec) who was converted at a revival meeting at the age of 23 and felt a call to preach. He attended a Methodist academy in Massachusetts before being ordained in Maine in 1833 at the age of 30. It was a time when there was great interest in work among the Native American tribes of the Northwest, building on a request from some Nez Percé tribesmen to help them find “the white man’s book of heaven”. This “Macedonian call” fired hearts and imaginations in the east, including Lee’s. Soon after, he

The Methodist story at Salem – Chemeketa, as it was known then – centers around Rev. Jason Lee, a native of Lower Canada (Quebec) who was converted at a revival meeting at the age of 23 and felt a call to preach. He attended a Methodist academy in Massachusetts before being ordained in Maine in 1833 at the age of 30. It was a time when there was great interest in work among the Native American tribes of the Northwest, building on a request from some Nez Percé tribesmen to help them find “the white man’s book of heaven”. This “Macedonian call” fired hearts and imaginations in the east, including Lee’s. Soon after, he

In those pre-Panama Canal days, a voyage by ship meant rounding Cape Horn at the tip of South America and putting in at the Sandwich Islands for reprovisioning and

In all, five mission posts would be established at The Dalles and Astoria on the Columbia, Nisqually on Puget Sound, and the Falls of the Willamette, with the headquarters based at Chemeketa (Salem). The goals were clear enough: bring the Native peoples to Christ, provide Western-style education, and offer improved techniques in agriculture, medicine, and homemaking. Lee’s original five missionaries would be supplemented by additional waves or “reinforcements” of missioners from the East, the first of which brought Lee’s future wife, Anna Pittman, to Chemeketa aboard the Lausanne, dubbed “the Mayflower of the West” for its role in transporting pioneering religious settlers. Anna Pittman embraced the missionary life for which she had volunteered, though she died after only one year at the mission, three days after giving birth to a son. The baby also died, very shortly after coming into the world. The poignancy of their story is mirrored in others’, as well; but the faith and commitment of Anna Pittman Lee, as well as her fervent love for God, her husband, and the peoples among whom she had settled, comes through in her letters back home to her family in New York. They are a testimony to a strong woman’s high sense of calling, zeal for active holiness, and courageous enthusiasm in a rugged and dangerous environment.

In some ways, the Methodist mission was something less than a great success. The total number of Native Americans reached for Christ was small: at

While unsuccessful as measured by the number of converts, the Methodist missions maintained friendly relations with the local tribal people. The school at Chemeketa turned first into an orphanage for parentless Native children, and later formed the core of today’s Willamette University. The Methodist missions played a critical role in the development of the Oregon Territory, and the first plat for a town center at Salem was laid out by missionaries. It was in 1849, just a few years after Lee’s death, that the Oregon and California Mission Conference was established, which would deploy circuit riders to bring the word of God throughout the region. The Willamette mission at

What you have just read is but the smallest sampling of a history that is displayed with surprising depth and texture at the Willamette Heritage Center. Visitors can see the restored Jason Lee House, which served as the mission headquarters, along with the original parsonage for the Methodist Episcopal Church in Salem. Nor do the Methodists have a lock on the religious history: Pleasant Grove Church, a tiny frame building used by the earliest Presbyterians in the region (among others) is open to the public during visiting hours. Also at the site is the old Thomas Kay Woolen Mill, for decades one of the major employers in the area, and now a rare setting for learning about the processes used in a traditional water-powered textile. The visitor center offers informational exhibits on the Native American tribes in the area, and their lives before and after the coming of European and American settlers. A museum store, along with a collection of other boutiques, provides a historical and quintessentially Oregonian shopping experience.

The Willamette Heritage Center offers plenty of free parking

It is rare indeed to learn so much about the work of the church at a non-church-related site. But the Willamette Heritage Center is a must-see for those interested in the development of mission work generally in the old Northwest, and of Methodist outreach in particular. Plan on a visit to the place where once heaven was “as near as at home”; you can almost catch the whisper of fervent prayer and the echo of Native children singing in the midst of the old shade trees.

Rev. Charles L. Harrell, Ph.D., is a retired elder in the Baltimore-Washington Conference. When not working at his day job as Director of Pastoral Care for a fabulous area retirement community or teaching in the field of history and doctrine at one of our United Methodist seminaries, he can often be found poking around sites of historical or cultural interest. His not-so-hidden agenda is to incite or fan a similar flame of appreciation for our heritage in faith and its gifts and promise for blessing now and tomorrow.