Traveling the Circuit: A Trio of Historical Places in Northern Virginia

By Rev. Charles Harrell

There are three places on the Virginia side of the Potomac that the savvy Methodist won’t want to miss.

Say “Old Town Alexandria,” and the mind goes to trendy restaurants, heritage buildings, or maybe places where General Washington lay his head. It’s also home to several significant sites in African-American history, one of which is a true landmark of United Methodist heritage.

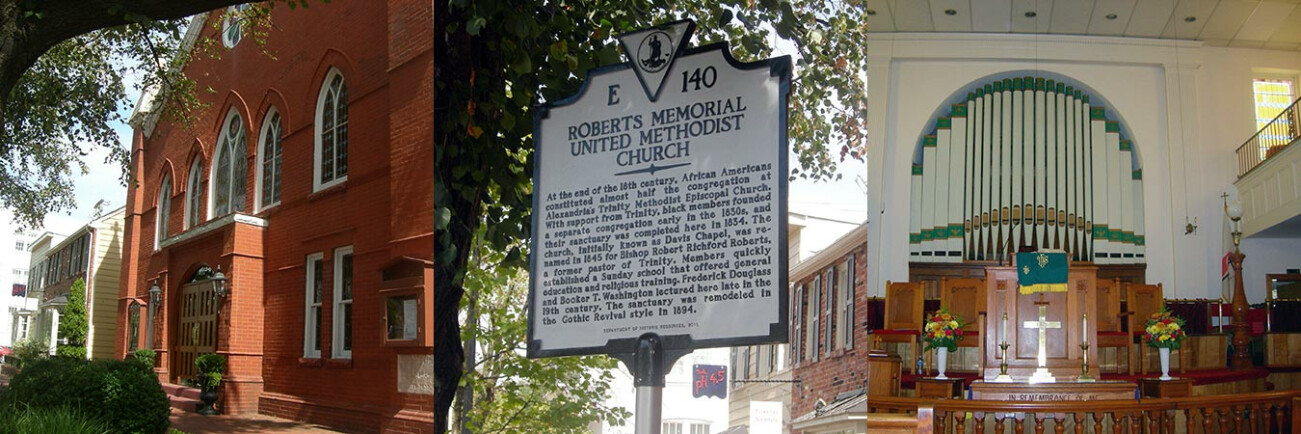

Roberts Memorial United Methodist Church, at 606A South Washington Street, was built in 1834 by Methodists who had come out of Trinity Methodist Episcopal Church some years earlier, making it the oldest black Methodist congregation in Alexandria. Locating their building between what were two black neighborhoods, the founding

Roberts Chapel was extensively remodeled in 1894, a period when many Methodist congregations were seeking a more prosperous look in an effort to appeal to a broader audience. To the two-story sanctuary was added a new Gothic Revival facade, complemented inside by a narthex and a magnificent period pipe organ built by Wilson L. Reiley of Georgetown. The decoratively-stenciled six-rank instrument was originally manually pumped; now it is played just on special occasions.

In addition to its worship and Bible study ministry, today’s Roberts Memorial Church is known for its outreach to the city’s poor, and its social justice and disaster relief work. In tribute to its deep roots and wider significance, the Commonwealth of Virginia dedicated a state historical marker outside the building in September. But don’t let its landmark status fool you; the current pastor, Rev. James Daniely, describes Roberts Memorial as a church on the move, with a special talent for hospitality. Step inside the door, and you, the visitor, will sense both the proud heritage and the Spirit’s energy. (Call before you go to be sure it’s open: 703-836-7332.)

From Roberts Memorial, follow Washington Street north and it becomes the George Washington Parkway; after a lovely drive along the Potomac opposite the nation’s capital, you arrive in McLean, Virginia. Winding through one of its tonier neighborhoods, pull in by St. John Academy, a Roman Catholic school, to visit the grave of one of the most significant early Methodist preachers in America, in a tiny cemetery at 6422 Linway Terrace.

Follow the short trail up a little knoll from the streetside historical marker, and situated among the spreading shade trees is a tiny graveyard bordered by a neat iron fence. Among the mostly unmarked burials stands a solitary white obelisk, marking the graves of Rev. William Watters and his wife, Sarah Adams Watters. Watters, the first itinerant elder born in America (in 1751), served 16 years as a circuit rider in Maryland, Virginia, and New Jersey, and about 30 years in McLean, where he died in 1827. According to the marker, he was “fervent in spirit, prudent in counsel, abundant in labor, skilled in winning souls ... a workman that needed not to be ashamed. He was a pioneer leading the way for the vast army of American Methodist itinerants having the Everlasting Gospel to preach.” He also helped to bring peace between factions over a controversy in early American Methodism that threatened to split the movement in its infancy. Pause a moment to reflect, in the shade among the decorative dogwoods, and to give thanks for those intrepid and faithful souls who, alone or with their spouses, planted and nurtured a great work of God that continues to this day.

From McLean, make your way to the Dulles Toll Road and point your wheels toward Leesburg, Virginia. While Marylanders are rightly proud of the unique role of Baltimore’s Christmas Conference in organizing Methodism in this country, it is easy to forget that there is a whole prehistory with roots before Lovely Lane in 1784. A significant piece of that heritage is tied to the Old Stone Church, whose site and

The list of names connected with the Old Stone Church reads like a “Who’s Who” of earliest American Methodism. John Wesley’s Scottish friend, Rev. Thomas Rankin, reported “a deeply serious congregation” meeting here in 1775 – the result, it is believed, of the preaching of Robert Strawbridge. In 1770, a meeting house was constructed here, enlarged in 1790 and dedicated at a service presided over by Wesley’s emissary Rev. Joseph Pilmoor. In February of 1776, Francis Asbury preached here, and two years later Methodism’s sixth conference in America was presided over by William Watters. After the Methodist Episcopal Church (an early name of our denomination) was formally organized, two annual conference sessions were held in the church: the Virginia Conference in 1790 (presided over by Bishop Thomas Coke), and the Baltimore Conference in 1812 (led by bishops Francis Asbury and William McKendree, the first American-born bishop). The cemetery also shelters the remains of worthies from the past: Captain Wright Brickell, one of American Methodism’s first book stewards (think “Cokesbury” of the 18th century); Richard Owings, first American-born local preacher who was converted under Strawbridge’s ministry; and lay preacher John Littlejohn, the Loudoun County sheriff who safeguarded the Archives of the U.S. during the War of 1812.

The interior of the old church was plain, with one decorative touch: an inscription of Genesis 16:13 on the chancel archway: “Thou

If your visit finds you in Leesburg at mealtime or if visiting heritage sites leaves you hungry, great options await close by. Lightfoot Restaurant, in a former bank building on N. King Street, just a couple of blocks from the church site, offers Zagat-rated American cuisine in an elegant environment. For more casual fare don’t miss Shoe’s, also on N. King, serving all three meals and offering al fresco outdoor seating in their “secret garden” via an adjacent alleyway. With trendy and regional options from salads and appetizers to sandwiches and plates, there’s something for most tastes. Craving just a snack? Check out the parmesan truffle fries (enough for two), or their fresh homemade ice cream. For variety, wash it down with root beer from Maine or cane-sugar Coke from Mexico.

Three different sites, three perspectives on the Methodist heritage, all doable in one pleasant day’s excursion not far from downtown Washington. It’s an excursion that spans more than 250 years in just a few miles. Don’t be surprised if, amid the old stones and under the spreading oaks, you hear a whisper that inspires your faith, or challenges your perspective, and sends you back to the here and now, to the place where you lay your head, perhaps a little different and much richer for having made the trip.

Rev. Charles L. Harrell, Ph.D., is a retired elder in the Baltimore-Washington Conference. When not working at his day job as Director of Pastoral Care for a fabulous area retirement community or teaching in the field of history and doctrine at one of our United Methodist seminaries, he can often be found poking around sites of historical or cultural interest. His not-so-hidden agenda is to incite or fan a similar flame of appreciation for our heritage in faith and its gifts and promise for blessing now and tomorrow.

You might want to add the gravesite of William Watters to your list. It's in McLean.