Remembering The Pearl: Church and its place in racial justice over the centuries

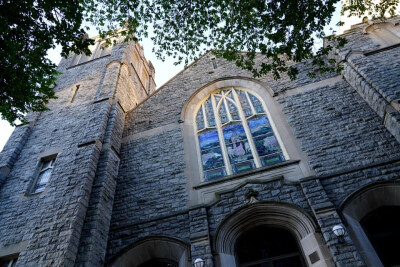

Asbury United Methodist Church sits right on K Street in downtown Washington, D.C. — a street full of some of the most powerful and well-connected lobbyists and advocacy organizations.

Asbury United Methodist Church sits right on K Street in downtown Washington, D.C. — a street full of some of the most powerful and well-connected lobbyists and advocacy organizations.

The gray stone church is home to a rich history. The church played a major role in the largest recorded escape attempt by enslaved people in the United States.

On April 15, 1848, a group of 77 slaves attempted to escape on a large sailboat called The Pearl. Abolitionists at the time hoped such a larger, daring escape would capture the attention of lawmakers and finally abolish slavery in the District of Columbia. At the time, slavery was still legal in Washington, D.C., but free Black folks outnumbered enslaved Black folks three to one.

The Pearl set out from what is now the Navy Yard neighborhood, hoping to travel down the Potomac River and up the Chesapeake Bay to New Jersey, a free state. But the winds fought against The Pearl, and the slaveowners using a steamboat caught up to The Pearl and took the enslaved people back to Washington, where pro-slavery riots broke out

Despite the unsuccessful escape, the Pearl Incident did spark some change within the District of Columbia. The Pearl Incident and subsequent riots spurred Congress to add the abolition of slavery in the Compromise of 1850, which mainly dealt with the status of nearly admitted western states into the United States.

Despite the unsuccessful escape, the Pearl Incident did spark some change within the District of Columbia. The Pearl Incident and subsequent riots spurred Congress to add the abolition of slavery in the Compromise of 1850, which mainly dealt with the status of nearly admitted western states into the United States.

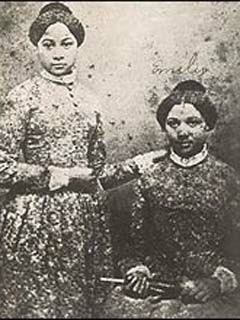

James Wright, the historian for Asbury United Methodist Church, said a number of members of the congregation took part in the abolition movement — and the Pearl Incident specifically — such as the Edmonson sisters.

But Wright emphasizes that, while Asbury United Methodist Church played a role in the Pearl Incident, it was more so a group of laypersons in the church, instead of an escape organized by the church.

“This idea has sprung up, which is not true, that Asbury was like the catalyst for the pearl incident,” Wright said. “It was not a catalyst. You just had members of the church who belong, who are involved in the incident.”

But dynamics within Asbury at that time of the Pearl Incident meant that — even though a number of Asburians were involved in the escape — the full extent of lay members’ participation in the incident was downplayed.

Even though Asbury was a predominantly Black church, its leadership at that time was white. Its leaders wanted to downplay the role its laypersons played in the incident, Wright said.

Other systems, though, within the church also kept the historic role some Asbury congregants played in the Pearl Incident buried.

“A lot of the African American history of the church, which is quite rich, is overlooked,” Wright said. “Remember something else about the church at that time. It was sort of split between slavery and free, north and south. So there was that schism there that kind of put a damper on the Black history there.”

Wright also pointed to a structure in place within the United Methodist Church until 1969: Central Jurisdiction. That organizational structure segregated all Black churches within the denomination into their own conference. No matter if a Black church was in Seattle or Birmingham, it was a part of the Central Jurisdiction, Wright said.

In the decades since the end of the Central Jurisdiction, more of Black church history is coming to the surface. Conferences across the United Methodist Church are learning of the vibrant history Black churches have held throughout the centuries.

“Because of the racial history of the church, people are now beginning to acknowledge that,” Wright said. “They’re beginning to study it a lot more, and there is now studying the black churches even more.”

Efforts to memorialize the escape continue even nearly two centuries later.

In 2017, a street in Washington, D.C.'s Southwest Waterfront neighborhood was named "Pearl Street" to commemorate the historic escape. And Asbury United Methodist Church was one of 40 sites or organizations to receive a $3 million grant in July 2021 from the National Trust for Historic Preservation’s African American Cultural Heritage Action Fund.

The grant was for repairs to the church’s wood windows and Bell Tower masonry, along with repointing and cleaning its stone facade

Whether it’s reproductive rights or LGTBQ rights, Wright said, it’s important to learn from the past to learn about the current struggles for rights. Church, he said, is more than an hour on Sunday.

“It's important for all people in The United Methodist Church to understand the true racial history of the church,” Wright said. “It's important for young people to understand that being a part of a church is not a stagnant experience, but it's a struggle.”

“It's important for people to understand it's not just about coming to church and sitting in the pew and praising and worshiping God from 2000 years ago. It's about what is going on now.”

Thank you so much. The story is so interesting. I am a member of Asbury Broadneck United Methodist Church in Annapolis, Md.

Thank you for this article. As an African-American historian, I heard about The Pearl, and also Asbury's rich heritage/contribution to African Americans in Washington, DC. Several members of my family (Dow descendants) were members of Asbury UMC that are no longer with us.

It is so important to continue digging into the past which can be passed on to the next generation. We have many more miles To go.