Church uses author’s life to reach youth

By Melissa Lauber

UMConnection Staff

As a pastor, the Rev. Vivian McCarthy is always listening for what’s going on in the life of the community as it unfolds around Reisterstown UMC. Recently, she heard a story that was helping to shape the moral imagination of the people in her church and beyond.

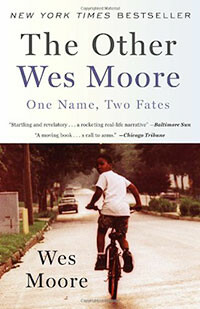

The story was told in a New York Times best-seller, “The Other Wes Moore.” Two young boys named Wes Moore were born in Baltimore, just blocks apart, within a year of each other. Both grew up fatherless in similar troubled neighborhoods and had difficult childhoods. One of them, the author, grew up to be a Rhodes scholar, a decorated veteran and a White House fellow. The other ended up a convicted murderer serving a life sentence in Jessup.

The story was told in a New York Times best-seller, “The Other Wes Moore.” Two young boys named Wes Moore were born in Baltimore, just blocks apart, within a year of each other. Both grew up fatherless in similar troubled neighborhoods and had difficult childhoods. One of them, the author, grew up to be a Rhodes scholar, a decorated veteran and a White House fellow. The other ended up a convicted murderer serving a life sentence in Jessup.

Their common journeys, how their paths diverged and the relationship they forged forms the foundation of the book.

“The Other Wes Moore: One Name, Two Fates,” was featured in Franklin High School’s “One Book, One Community,” initiative last summer and read by every student and teacher in the Reisterstown school.

Reisterstown UMC was going through some struggles and McCarthy decided she needed to preach a series on coping. The story of the two men named Wes Moore came to mind.

On Jan. 10, she preached the sermon, “Keep Calm and Trust God.” In her preaching, she stressed Moore’s quote: “The chilling truth is that his story could have been mine, the tragedy is that my story could have been his.”

McCarthy led the congregation through the truth highlighted in the book that “small decisions become big decisions.”

The story took on an extra and tragic poignancy because the man who was killed in Wes Moore’s robbery was Baltimore County police Sgt. Bruce A. Prothero, a loving husband

According to the Baltimore Sun, Prothero was shot three times Feb. 7, 2000, as he chased four men out of a jewelry store during a robbery at the store, where he was working a second job as a security guard.

Moore was convicted of felony murder later that year, based on testimony that he and his half-brother held a clerk and customer at gunpoint while two accomplices smashed jewelry cases and fled with more than $400,000 in watches.

McCarthy remembers when Bishop Felton May, then the resident bishop of the Baltimore-Washington Conference, returned from Prothero’s funeral service. He spoke of policemen lined up for more than a mile to honor the officer.

Prothero’s death shook the community and the emotional and spiritual pain lingers.

Wes Moore

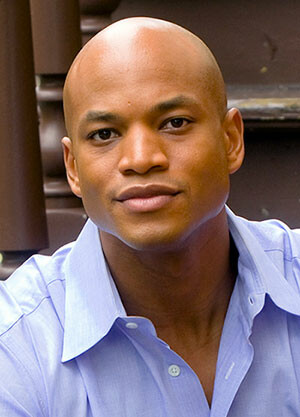

In her listening to the community, McCarthy had heard that the school invited Wes Moore, the author, to speak to the students. He was unable to do so. But McCarthy thought she might have something to contribute, so she contacted the author’s representatives and told them the compelling story of how the church and community were connecting to the book. She shared what a difference it might make for the author to bring a message of the two Wes Moores to youth struggling with choices, consequences and the many factors that lead to success or failure.

His executive assistant heard McCarthy’s plea and Moore agreed to wave his more than $25,000 speaking fee.

The church paid a portion of Moore’s travel expenses and bought each student a copy of his new novel for young adults.

The money came from a grant managed by the church library at Reisterstown UMC.

On Feb. 18, Moore spoke at Franklin High School. “The kids were entranced, they were riveted on what he had to say,” McCarthy reported. “Wes answered questions and the kids stood in line, some for an hour-and-a-half, to get their books signed. He took pictures with the kids and talked to them like they were the only person in the room.”

The next Sunday, Reisterstown UMC had more than 260 people in

McCarthy doesn’t know if they attended because of the church’s involvement in bringing Moore to speak to the high school students, but she celebrates the church being willing to reach out and be a part of the community’s story.

At one point in the book, the other Wes Moore visits his mother’s church and is unable to connect. He recounts a moment of despair and anger where he says, “If he does exist, he sure doesn’t spend any time in West Baltimore.”

McCarthy is glad the church is willing to genuinely wrestle with the difficult realities facing the community. “It is truly a God moment,” she said.

In the promotional materials for the book, it’s noted that in December 2000, in the same issue of the Baltimore Sun, there was a small story of Wes Moore receiving a Rhodes scholarship and, just pages away, the story of a manhunt for the killers of a police officer – one of whom was named Wes Moore.

As she worked on her sermon and Moore’s speaking engagement, the factors that led these boys to live out such different stories fascinated McCarthy. It’s her prayer that the church will be present in ways that illuminate good choices for today’s youth.

“Our daily life is what we have to give back to God,” she said. “It is often messy and doesn’t always sound very spiritual, but it’s our gift to God nonetheless.”