Ministries & Resources for Vitality

All ministries and resources of the Baltimore-Washington Conference support congregations and leaders to achieve 100% vitality and bridge the gap between where we are and where God is calling us to be. A vital church isn't determined by church size, money, number of programs or the latest technology. Vital churches see and respect all people; deepen discipleship; live and love like Jesus; and multiply and grow their impact.

See All the People | Deepen Discipleship | Love Like Jesus | Multiply Impact | Develop Leaders

See & Respect All the People

See & Respect All the People

Building authentic relationships so that people inside and outside of the church are known, accepted, respected and valued as children of God.

Deaf Ministry

Communicate with and include people who are deaf and hard of hearing in worship and other ministries.

Disability Ministry

Welcome all people to Christ's table, using an accessibility audit and other resources to provide loving accommodations for all God's children.

Multicultural Ministry

Deepen relationships and ministries with African American, Hispanic-Latino, Korean, and Native American communities.

Young People's Ministries

Activate, connect and engage more youth and young adults as disciples of Jesus.

Deepen Discipleship

Deepen Discipleship

Creating paths for more people to witness Jesus Christ through acts of justice, compassion, devotion, and worship under the guidance of the Holy Spirit.

Camping & Retreats

Play, grow, connect and thrive at three locations for life-changing summer camp experiences and in retreat settings for individuals and groups.

Campus Ministries

Link students with God and the church through United Methodist ministries at five area colleges and universities and learn more about scholarships.

Discipleship Development

Assist your church in making and nurturing disciples of Jesus Christ.

United Women in Faith

Gather women to foster spiritual growth and serve in mission around the world.

Live & Love Like Jesus

Live & Love Like Jesus

Taking the Gospel beyond the walls of the church to serve the poor, heal the heartbroken, set the oppressed free and comfort all who mourn.

Creation Care

Connect to protect and be good stewards of all of God’s creation.

Connect to protect and be good stewards of all of God’s creation.

Gender Equity / COSROW

Address gender discrimination and sexism, and raise awareness of sexual ethics.

Address gender discrimination and sexism, and raise awareness of sexual ethics.

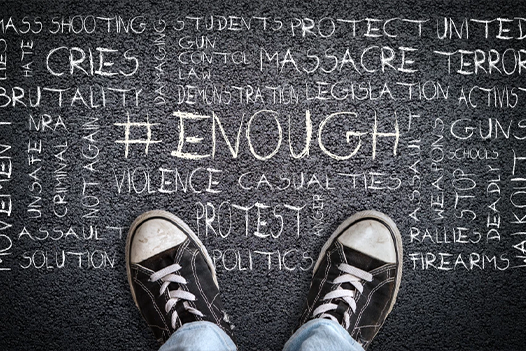

Gun Violence Prevention

End the violence caused by firearms through education and legislation.

End the violence caused by firearms through education and legislation.

Legislative Advocacy

Lobby and work for changes in laws, systems and structures in order to love others.

Lobby and work for changes in laws, systems and structures in order to love others.

Peace with Justice

Create God’s shalom through social justice ministries and apply for grants through Peace with Justice Sunday offerings.

Create God’s shalom through social justice ministries and apply for grants through Peace with Justice Sunday offerings.

Restorative Justice

Support and aid those involved in the criminal justice system.

Support and aid those involved in the criminal justice system.

Racial Justice / CCORR

Ensure the fair treatment of people of all races and seek equitable opportunities and outcomes for all.

Ensure the fair treatment of people of all races and seek equitable opportunities and outcomes for all.

Wellness & Missions

Foster abundant life in individuals and communities and respond with relief efforts and in mission to those facing hardships and disaster.

Foster abundant life in individuals and communities and respond with relief efforts and in mission to those facing hardships and disaster.

Multiply Impact

Multiply Impact

Listening and discerning with the broader community to reshape church ministry and repurpose resources for the greatest good.

Church Planting

Equip and deploy lay and clergy to star and sustain new and vital congregations through Path 1.

Congregational Development

Empower your church to grow in vitality through the Catalyst or Readiness initiatives.

Missional Innovation

Become inspired and catch an entrepreneurial outlook as you create new ways of being church.

New Faith Expressions

Generate new and creative faith communities born out of the context of people’s lives.

Develop Leaders

Develop Leaders

Developing mature Jesus followers, both lay and clergy, who use their gifts to build up the body of Christ for the transformation of the world.

Center for Vital Leadership

Nurture disciples to lead self, others and organizations in vital and transforming ways.

Clergy Development

Equip pastors to live out God’s call to set-apart ministry and effectively lead congregations.

Congregational Development

Empower your church to grow in vitality through the Catalyst or Readiness initiatives.

Lay Servant Ministries

Engage lay people to serve the church as they proclaim the Good News and reach out to others in love.

Training Tuesdays

View a vast archive of webinars to inspire and equip local church leaders.

Leader Nominations

Respond to God’s call by serving on a BWC committee or ministry.

Looking for Answers?

If you are not sure where to start or how to find the resources your congregation needs,

take a look at the leadership directory for a list of knowledgeable people you can contact based on what you are looking for!