'To live to God:' Asbury in America

At the 160th meeting of the Baltimore-Washington Conference Historical Society, John Strawbridge provided an illuminating look into the mind and heart of Bishop Francis Asbury and his ministry that spanned 300,000 miles and brought forth a Church in the New World. The meeting was held Sept. 10 at Lovely Lane UMC in Baltimore. The text of his address follows:

Rambles through the United States: Asbury in America

It is Thursday, September 12th, 1771 – a

It is Thursday, September 12th, 1771 – a

“I will set down a few things that lie on my mind. Whither am I going? To the New World. What to do… To gain

The man has left England penniless, but at the last

“Many have been my trials in the course of this voyage; from the want of a proper bed, and proper provisions, from sickness, and from being surrounded with men and women ignorant of God, and very wicked. But all this is nothing. If I cannot bear this, what have I learned? Oh, I have reason to be much ashamed of many things, which I speak and do before God and man. Lord, pardon my manifold defects and failures in duty.” 2

With such a poor start to his

Asbury’s Challenge

When this young man, Francis Asbury, arrives in Philadelphia on October 27th, perhaps he feels a bout of homesickness. Maybe he’s thinking about his parents, keeping a place for him back home in the little brick cottage on Newton Road. Maybe he’s thinking about the self-assurance of his mentor, John Wesley, and about how confident he himself had felt back in August when he had volunteered for this “visit.”

Asbury feels that he has been sent not by Wesley, but by God. He believes that God had made the last six months of his life in England very difficult … in order to make him more willing to leave home and find his purpose. He believes God had given him, like Jonah, a push, where he himself had been too afraid to jump.

But having reached his destination Asbury writes in his journal of a more hopeful vision:

“When I came near the American shore, my very heart melted within me, to think from whence I came, where I was going, and what I was going about… I find my mind drawn heavenward. The Lord hath helped me by his power, and my soul is in a paradise. May God Almighty keep me as the apple of his eye, in all the storms of life are past! Whatever I do, wherever I go, may I never sin against God, but always do those things that please him!” 3

In this exuberance, Asbury seems ready for anything. But in this early day, he does not yet know … that he will never return to the country that he thinks of as home. Indeed, he does not know that he will never again have any home at all, but will spend the next forty-five years on the road -- riding from place-to-place -- sometimes more than 6,000 miles in a year, almost 300,000 miles altogether. An achievement that will earn him the nickname “Prophet of the Long Road” – bestowed on him by later generations. Asbury, in the humility and doubt of his own mind, will christen himself: “this man that rambles through the United States.” 4

Asbury’s American mission may have been set in motion by John Wesley, but almost from the moment that young Francis set foot on the ground of the new world, it became a journey in a direction very different from the destination that Wesley intended.

Wesley was, and remained for his whole life, a reformer. His goal was to set right what he felt was the misguided and corrupted church of his father and grandfather. But even though the Anglican Church in America was also flawed, even these flaws were manifest in markedly different problems than those which plagued the mother country.

Wesley hoped that his missionaries would bring reform to the colonial church while it was still in its infant stage … that Asbury and others might bring a measure of discipline and – indeed – Method to what was seen as a disorganized collection of provincial congregations; which were no doubt starving for guidance and meaningfulness.

But what Francis Asbury was to discover in America was that

In 1793, Asbury would find himself accused of failing in his appointment. He answered the charge in this way:

And why was I thus charged? Because I did not establish Mr. Wesley's absolute authority over the American connexion: — for myself, this I had submitted to; but the American's were too jealous to bind themselves to yield to him in all things relative to Church government. Mr. Wesley was a man they had never seen — was three thousand miles off — how might submission, in such a case, be expected? Brother Coke and

And there was another force working to draw Asbury away from Wesley’s plan – the will of God Himself. Asbury makes clear in his journals that… though he respects Wesley, whom he refers to as “that venerable father in Christ,” 6

If Francis

Typical of where he finds his vast new parish, in a Nov. 5, 1772 journal entry, Francis Asbury, while traveling in “Strawbridge Country” writes:

“The

At the first official American Conference at St. George’s in Philadelphia in 1773, Asbury is assigned to the Baltimore preaching circuit – then the densest population of Methodists in America. This was due to the work of another preacher assigned to the Baltimore City Station along with Asbury; Robert Strawbridge.

Strawbridge and Asbury

Strawbridge is credited in Asbury’s journals as being the first preacher to establish Methodism in America. 10

Robert had been preaching and establishing Methodist classes in America since about 1761. It is his ministry Asbury refers to when speaking of the transformation of the swearers, liars

The Anglican Church had been established in Maryland by an act of law in 1692. As such, it was supported by a tax on the citizens of the

Thomas Bacon, the rector, was spending most of his time in the state capital working on a book titled; “Laws of Maryland” and so he had hired two curates to watch over his languid parish. Such would have been the neglected populace into which Robert Strawbridge found himself called. Like Asbury, Strawbridge felt his true call was from God, not man. And while Robert also demonstrates a passion for the Wesleyan model of Methodism and itinerant connexion, he was not sent by Mr. Wesley.

Robert and his wife Elizabeth moved to America as part of a tidal wave of immigration – a population explosion chasing opportunity in the new world. For Robert, it was an opportunity to spread Methodism to a new and spiritually famished populace.

Robert’s ministry filled a particular void in the spiritual life of American Methodists and people in general. As the American colonies moved closer to rebellion against the crown, the ministers of the King’s church found in prudent to remove themselves back to England. So people who might have seen an ordained preacher only once every three or four months under the best of

This became a much noted and discussed source of disagreement between Strawbridge and the American General Superintendent; Thomas Rankin… and then with Asbury as he came to America with what he felt was a commission from Asbury to bring order to the offspring land.

Asbury writes of his conversation with the German minister, Benedict Swope: “We had some conversation about the ordinances administered by Mr. Strawbridge. He advanced some reasons to urge the necessity of them… I told him they did not appear to me as essential for salvation, and that it did not appear to be my duty to administer the ordinances at that time.” 11

One month later, in speaking of the Dec 23,

But Wesley, too, had built his movement by flaunting the rules; preaching out of doors and out of his parish, often inciting riots and attacks against himself.

Such was the level of disruption that Wesley created, that he was called to explain himself to Bishop Butler of Bristol. Wesley, in his own transcription of the encounter, replied:

“As to my preaching here, a dispensation of the gospel is committed to me, and woe is me if I preach not the gospel wheresoever I am in the habitable world… When I am convinced that I do [break any rule], it will then be time to ask, ‘Shall I obey God or man?’”13

Wesley, like his father and grandfather before him, felt a personal freedom to act outside the laws of the Church as needed – even to the point of deciding that it was ecclesiastically appropriate for him to ordain Dr. Coke as a Superintendent (or bishop) though he himself was not. Strawbridge was perhaps more Wesleyan than Asbury – who followed God, the rules and Wesley in pretty much that order.

Wesley, so well-known for his methodical-ness and Discipline, would famously write:

“I am not afraid that the people called Methodist should ever cease to exist in either Europe or America. But I am afraid, lest they should only exist as a dead sect, having the form of religion without the power.” 14

And so, interestingly, Wesley shows the same spirit as Strawbridge… in not letting rules stand in the way of serving the needs of the people. In fact, the very founding of the Methodist movement is

But Asbury was fated… if I may employ so Calvinist a view… to have almost the opposite journey. Arriving only a decade after Strawbridge, Asbury found not a people restricted by

Wesley and Strawbridge had the freedom to be founders – pioneers in the faith of their respective lands. Asbury was doomed to that much more ignominious task – to be the administrator. To be the one to take the grand ideas and passions of those who went before him, and to turn them into workable systems and procedures.

Such was Asbury’s commitment to the comfort of dependable rules, that he eventually codifies even Strawbridge’s defiance into a kind of amendment. He wrote: “No preacher in our connexion shall be permitted to administer the ordinances at this time; except Mr. Strawbridge, and he under the particular direction of the assistant.” 15

Not that we should, in any way, discount Asbury’s pioneering efforts. His were the first preacher’s hoof prints in many a settlement. And many were brought into Methodism, if not into any life of faith at all, by Francis’ preaching. But where others were working outward from their start, Asbury always had his eye on a destination. He blazed trails with the goal of all roads leading home.

In this way, circumstances made it impossible that Asbury and Strawbridge should ever entirely be in agreement. Beginning at opposite ends of the road, they either rode in different

The work of Connexion can be a very complicated labor.

Companions on the Road: God and Satan

Asbury may have envied the confidence of Wesley and Strawbridge, and throughout his ministry and along his road, he finds himself plagued with the same doubts he experienced aboard ship; being beset by worries of his own weakness… and dependent on the strength of God to keep going.

Asbury may have envied the confidence of Wesley and Strawbridge, and throughout his ministry and along his road, he finds himself plagued with the same doubts he experienced aboard ship; being beset by worries of his own weakness… and dependent on the strength of God to keep going.

Consider this sampling of his journals for 1774:

January 15. My body is still weak, though on the recovery. Lord, if thou shouldst be pleased to raise me up, let it be to do more good! I desire to live only for this!

January, 19. My mind is kept in peace, though my body is weak; so that I have not

March 1. …my mind was oppressed above measure; so that both my heart and my mouth were almost shut: and after I had done, my spirit was greatly troubled. O

March 19. … Satan assaulted me powerfully with his temptations on Monday; but by calling on the name of the Lord, I was delivered.

April 11. I was somewhat better. But I find myself assaulted by Satan as well in sickness as in health, in weakness as in strength. Lord, help me to urge my way through all, and fill me with humble, holy love, that I may be faithful until death, and lay hold on eternal life.

October 11. Last night my soul was greatly troubled for want of a closer walk with God. Lord, how long shall I mourn and pray, and not experience all that my soul longeth for?

October 28. I do not sufficiently love God, nor live by faith in the suburbs of heaven. This gives me more concern than the want of health.

Satan appears to be a constant traveling companion for Asbury, and he is referenced 147 times in the journals – not as if

Worries will continue to follow Francis throughout his life, though perhaps at no time greater than during the years of the war of American Independence. Maryland… where Asbury was assigned to the Baltimore Circuit… required that its residents take an Oath of Fidelity which required taking up arms against England. For many preachers, this necessitated a return to England. Asbury couldn’t consider this; his work

“My usefulness appeared

So why… when every providence seems determined to direct Asbury to return home… does he remain on his difficult journey? An answer, or at least an insight into his mindset, can be found in his own words on Sunday 28 May 1780:

“Bless the Lord, who gives me to weep with them that weep! But O! what must my dear parents feel for my absence! Ah! surely nothing in this world should keep me from them, but the care of souls; and nothing else could excuse me before God.”

Doubt had plagued Francis all his life, and while recuperating in 1792 he recalled those feelings from the very first time he heard a Methodist preacher in his youth: “He talked about confidence, [and] assurance… of which all my flights and hopes fell short.”

He continues: “On a certain time when we were praying in my father's barn, I believed the Lord pardoned my sins and justified my soul; but my companions reasoned me out of this belief, saying, ‘Mr. Mather said a believer was as happy as if he was in heaven.’ I thought I was not as happy as I would be

A Restless Man

There is, throughout Asbury’s journals, a sense of desperation and restlessness. He stops in any one place only when the weather or his own infirmity requires it. Perhaps Francis found his native land too well ministered, for he takes to the American roads like an addict – seeking out any and every pocket of wantonness and wickedness.

And America obliges; providing Asbury with an abundant crop of sinners. From the very beginning of his journey, he writes to his parents, “I have found at length that Americans are more willing to hear than to do; notwithstanding, there is a considerable work of God.” 18

He laments that he has been sent to the place where

Even two years later, Asbury describes the people Baltimore in this way:

“I spent some time in town and was greatly grieved at the barrenness of the people; they appear to be swallowed up with the cares of the world.”20

On another occasion, he disparages the people come to hear him as “a large company of people collected, who appeared both ignorant and proud.” 21 At other times, he describes the people and congregations he encounters with the words; dull, disorderly, sleepy, languid, insensible, wicked, and hard in their minds. And on July 1st of 1772, he finds himself in

Asbury’s constant see-saw of despair and hope never abates, as is evident in 1793 when he writes about his emotions upon visiting the ruins of the orphanage established by George Whitefield: “A wretched country this!—but there are souls, precious souls, worth worlds.” 23

But if Asbury believed the American populace was set to drive him to despair, he found that the land itself was keen to hinder, wound or even kill him:

February 21, 1773. “The water froze as it ran from the horse’s nostrils…”

March 11, 1774. “On my way to Joseph Presbury's my horse tired, and fell down with me on his back…”

February 4, 1793. “After dinner I met with [a man] who offered to be our guide; [he said he had killed a Negro worth sixty pounds, and a valuable horse with racing.] but when I began to show him his folly and the dangerous state of his soul, he soon left us, and we had to beat our way through the swamps as well as we could.”

January 20, 1794. “The American Alps, the deep snows and great rains, swimming the creeks and rivers, riding in the night, sleeping on the earthen floors, more or less of which I must

When Asbury writes those words, he has been on his American “visit” for twenty-three

For Asbury, no adversity was worse than the unknown. An avid student, he studied Greek, Latin

Far From Home

Such attraction to the shadowed places puzzled those comfortable at home. In a letter to Asbury’s mother dated August 27, 1771, four women of the town inquire:

“We have heard that your son is going, or is gone, to America. … We think it must be an instance of much trouble to both, for indeed we were very much grieved when we heard Mr. Asbury was going there… if he is gone; for we can scarce believe he is so mad…” 26

At first, Asbury and his parents wrote to each other often, although not every letter reached its destination. Early on, Asbury spoke often of returning home – but his musings sound half-hearted – intended more to reassure his worried parents than like any real plan. Though he complained about it, Asbury relished the work in America.

In a letter dated October 7,

“You would not have me leave the work God hath called me to, for the dearest friend in life. If the flesh will, your spirit will not. However, you may depend upon it, I will come home as soon as I can: but he that believeth shall not make haste. As I did not come here without counsels and prayers, I hope not to return without them, lest I should be like Jonah.” 27

And again in the fall of 1773, he says, “When I consider the order and steadfastness of my own country friends, I wish almost to be with them… I hope to be in England in less than two years.” 28

But ten years later, he is no closer to sailing back to England. In August of

In May of 1784, he writes in his journal: “I learned by letter that my father and mother are yet alive.” 30 It is almost an afterthought in a longer entry. Pleasant, but little affecting.

Step by step, Asbury’s connexion to the new world Methodist overshadowed his connection to his home life.

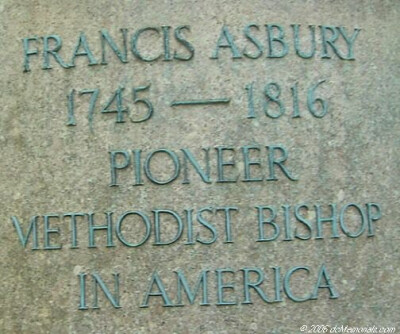

In 1784, the year after the conclusion of the war for American Independence, the American Methodists’ entreaties to John Wesley finally come to fruition, and Wesley abandons his hopes for the King’s church in the new world and reluctantly agrees to the founding of Methodism as a new and independent denomination in America. Wesley dispatches Dr. Coke, along with Richard Vasey and Thomas Whatcoat to set aside Asbury and Coke as the first Superintendents of the new American church.

But Asbury has already “gone native” and protests that it would be un-American to be so appointed. He insists upon being elected. And so on the first day of the Christmas Conference at the Lovely Lane Meeting House in 1784, Francis Asbury is elected as a deacon. On the second

And on the third day, his brethren elect him Superintendent – a title he and Dr. Coke will soon change to Bishop.

In addition to his almost daily, and sometimes twice daily, preaching – Asbury is now caught up in the business of establishing and governing a new church. It is a time of great productivity and focus – but not of looking

Two and a half weeks after learning that his parents are “yet alive,” Asbury finally writes to them:

“It gave me some comfort to hear of you, by the kind and friendly hand of Mr. Boon, the first direct account I have received from you these seven years. My anxiety of mind would have been great for this; and my seeming disobedient

In this same letter, he explains that since he cannot return home, he considers bringing his parents to America – but immediately and somewhat unconvincingly expounds on a

Asbury changed little, even as the world around him changed much. As the colonies became a country… as a movement of two thousand Methodists grew into a church of two-hundred thousand… and as he himself went from being a lay preacher to being the bishop and spiritual father to a generation… Asbury remained a traveling preacher. Struggling to bring the Word to the unenlightened, and wrestling with his own sense of doubt and self-worth.

Asbury is heroic, but he is no hero. His greatness lies in his weakness... in his ordinariness. He is all the more admirable for forging on knowing the size of the obstacles, trusting more in God’s work than in his own. He fulfilled his own prophecy: gaining neither great honor nor wealth. He brought many to God as someone in whom the early converts could see themselves… Could see that a man with weakness, illness

The Preacher At Day’s End

Francis Asbury died on March 31st, 1816 while preparing to make the journey back to Baltimore to attend Conference. He was buried in Spotsylvania, Virginia. In May, the General Conference ordered that his body

Francis Asbury died on March 31st, 1816 while preparing to make the journey back to Baltimore to attend Conference. He was buried in Spotsylvania, Virginia. In May, the General Conference ordered that his body

It was planned that he would be buried under the pulpit recess of the Eutaw Street Church (also a part of City Station) and so his casket was carried through the streets. The funeral cortege between the Light Street Church and Eutaw Street Church was attended by over 20,000 people – more people

In 1845, Baltimore City Station established a new cemetery to become known as Mt. Olivet, and within the bounds of this God’s Acre was to be set aside a “Preachers’ Lot” for the burial of such “traveling preachers and their wives” as might wish to be buried there. In 1852, the Baltimore Conference & the General Conference directed that Asbury’s remains again be relocated there in what soon was renamed the “Bishops’ Lo.t” Thus, even in death, Asbury remained itinerant.

In June of 1854, with his burial at Mt. Olivet, Francis Asbury’s “Long Road” came to an end. Measured in a direct line, it was 3,538.38 miles from the cottage on Newton Road 32, and 109 years after it began. But the road was never direct, and years do not pass at the same rate from one end of our lives to the other. As long as we remember him; here today, and in the names of schools, churches, towns and even an amusement park, Asbury rides on.

Notes:

1 Asbury, Francis. Journal, 1771, September, 12

2 Asbury, Francis. Journal, 1771, October, 13

3 Asbury, Francis. Journal, 1771, October 27 and November 2

4 Asbury, Francis. Journal, 1793, January, 13

5 Asbury, Francis. Journal, 1793, January, 25

6 Asbury, Francis. Journal, 1773, June 14. For another example, on 1772, September, 29, he writes; “The reading of Mr. Wesley’s journal has been made a blessing to me…”

7 U.S Census Bureau, “Historical Statistics of the United States: Colonial Times to 1970,” which cites as its main sources reports by Colonial officials to the Lords Commissioners of Trade and Plantations in London, censuses conducted in individual Colonies, militia records, tax liens and estimates by Colonial officials themselves, as quoted on

8 National Army Museum,

9 Asbury, Francis. Journal, 1772, November, 5

10 Asbury, Francis. Journal, 1801, May, Thursday, 30

11 Asbury, Francis. Journal, 1772, November, 22

12 Asbury, Francis. Journal, 1772, December, 22

13 Among other sources, see Hurst, J.F. and Joy, James Richard. “John Wesley the Methodist, A Plain Account of His Life and Work”, By a Methodist Preacher, Chapter IX, The Methodist Book Concern, 1903

14 “Thoughts upon Methodism” – John Wesley (London 4,

15 Asbury, Francis. Journal, 1773, July, 14

16 Asbury, Francis. Journal, 1778, September, 15

17 Asbury, Francis. Journal, 1792, July, 16-19

18 Letter to My very dear Parents, October 7, 1772, Quoted in The Methodist Magazine and Quarterly Review, 1831

19 Trevelyan, G.M. “History of England”, Chapter II, pg. 234, Doubleday & Co.

20 Asbury, Francis. Journal, 1774, December, 4

21 Asbury, Francis. Journal, 1774, March, 1

22 Asbury, Francis. Journal, 1772, July, 1

23 Asbury, Francis. Journal, 1793, Feb, 2 [Whitefield’s Bethesda Orphanage est. 1740, burned down 1773]

24 Letter to Dear Mother and Father, January 24, 1773, United Methodist Archives, Drew University Library

25 Asbury, Francis. Journal, 1792, July, 16-19

26 Letter to Mrs. Asbury, August 27, 1771, United Methodist Archives, Drew University Library

27 Op. cit. Letter, October 7, 1772

28 Letter to My dear Parents, September 5, 1773, United Methodist Archives, Drew University Library

29 Letter to George Shadford, England,

30 Asbury, Francis. Journal, 1784, May, 20

31 Letter to My dear Parents, June 7, 1784, United Methodist Archives, Drew University Library

32 As measured on Google Earth, distance from Bishop Asbury Cottage, Newton Road, Great Barr, Sandwell, West Midlands, B43 6HN, UK to Bishop Asbury’s grave in the Bishops’ Lot, Mt. Olivet Cemetery, 2930 Frederick Avenue, Baltimore, Maryland, 21223, USA